Charles Walter Clewell (1876-1965) was a visionary metalworker and artist who developed a method of coating pottery with metal and treating the finish to produce a rich brown patina accented with vibrant shades of verdigris, blue and orange. Clewell also had a keen eye for graceful, well-proportioned shapes that complemented his extraordinary finishes.

Clewell’s work is firmly rooted in the Arts and Crafts aesthetic. The Arts and Crafts movement originated in nineteenth-century England as a reaction against the mechanized production and excessive ornamentation of Victorian-era furnishings. Taking its name from the Arts and Crafts Exhibition Society founded in London in 1888, the movement emphasized simplicity, beauty and utility of design, with the overarching goal of restoring dignity and creativity to the applied arts.

In the Arts and Crafts movement, “[w]ell-proportioned forms grew organically from a clean and direct expression of function, structure, and the nature of material; the result was that the new objects brought man back in touch with himself.” (Beth Cathers (with Tod M. Volpe), Treasures of the Arts and Crafts Movement 1890-1920, p. 8 (1988). This aptly describes Clewell’s work. (For a description of the goals of the Arts and Crafts movement and their adoption in the United States, see Wendy Kaplan, “The Art That is Life”: The Arts & Crafts Movement in America, 1875-1920, pp. 298-306 (1987).)

In the early 20th century the Arts and Crafts movement flourished in the Midwest, thanks to potteries such as Rookwood, Roseville and Teco. Residing in Canton, Ohio, Clewell found himself in a hotbed of artistic creativity, and made his own significant contribution to the Arts and Crafts movement. Starting in 1906, he obtained bisque (fired but unglazed) blanks from area potteries including Owens, Weller and Ferock, and developed his oxidation process using minerals such as chrysocolla, cuprite, malachite and azurite.

According to an undated promotional leaflet entitled “The Bronze Productions of C.W. Clewell of Canton, O.”, he was inspired by a bronze wine jug dating from 200 B.C., which he saw at the Wadsworth Atheneum in Hartford, Connecticut. It was “a wonderful blue, varying from the very light tones through turquoise to almost black, with flecks of green and rust-like brown and spots of bare darkened metal.” This led him to “more than two years of experimenting and a number of trips to Hartford to compare results, [until] finally the perfect blue appeared.”

According to an undated promotional leaflet entitled “The Bronze Productions of C.W. Clewell of Canton, O.”, he was inspired by a bronze wine jug dating from 200 B.C., which he saw at the Wadsworth Atheneum in Hartford, Connecticut. It was “a wonderful blue, varying from the very light tones through turquoise to almost black, with flecks of green and rust-like brown and spots of bare darkened metal.” This led him to “more than two years of experimenting and a number of trips to Hartford to compare results, [until] finally the perfect blue appeared.”

Clewell worked alone and never divulged his methods; thus little is known even today about how he produced such distinctive results. The promotional leaflet contains only a poetic general description of the process: “New bronze … aided by time, heat and cold … takes from the air, the water and the earth, elements to produce the iridescent tarnishes, the reds, all shades of brown, somber purple or deep, bottomless black. … creeping corrosion gradually [creates] infinitely varying shades and tints of blue and green: the ‘Aerugo Nobilis’–noble rust of bronze–as the Romans named it, long ago.”

As Clewell acknowledged, one of the keys to his success was his ability to arrest the oxidizing process when the desired patina was achieved: “Chemical treatment to induce these colors to appear and spread and grow, waiting until they have reached the point of greatest beauty in their contrasts with the tarnished, darkened metal surface, then stopping the chemical action and fixing the colors so that they may remain forever unchanged, this has been his work.”

Although Clewell’s metal coatings are usually described by auctioneers as copper, the leaflet proclaims that he used bronze for his coatings: “BRONZE, in art, may be either pure copper or an alloy of copper and tin.”

While he is not one of the most famous makers of American art pottery, Clewell’s solitary, sedulous labors produced a legacy of thousands of desirable pieces, no two of which are the same. The leaflet states, “In color each bronze is unique for no two can possibly have identical patinations. Sometimes there are well-matched pairs, but even then each has its own particular individuality. The owner of a Clewell bronze may be sure that nowhere is there an exact counterpart.”

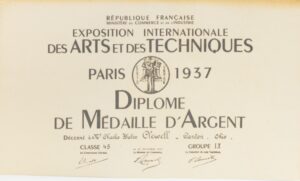

Clewell was elected as a Mastercraftsman by the Council of the Society of Arts and Crafts of Boston, an organization that was instrumental in establishing the Arts and Crafts movement in the United States. In 1937 Clewell received a medal at the Paris Exposition.

Clewell was elected as a Mastercraftsman by the Council of the Society of Arts and Crafts of Boston, an organization that was instrumental in establishing the Arts and Crafts movement in the United States. In 1937 Clewell received a medal at the Paris Exposition.

Clewell died in 1965 at the age of 89.

Clewell also produced tableware which did not undergo the same patination process. Such items are outside the scope of this website.

What Makes Clewell Special?

Most art pottery uses contrasting colors to represent an object or figure, or simply as a highlight or accent. The singular quality that distinguishes Clewell’s work is his use of chemical reactions to produce bold colors, which are given center stage. His dramatic, variegated patches of green, blue, orange or red dominate large swaths of the piece, ceding to a robust metal base, producing a uniquely expressive and visceral effect.

Clewell was an indefatigable experimenter, and the interactions of the natural elements he harnessed were inherently somewhat unpredictable. Accordingly, as noted above, no two Clewells are alike. Some have little or no coloration (shapes 2-6, 209, 316-4, 363-4), while on others color overwhelms the metal base entirely (shapes 108, 272-5, 294-6, 351-9).

Clewell’s pieces evoke the beauty and infinite variability of nature. Yet he exercised restraint by keeping the patination simple, regular and more or less symmetrical, avoiding jarring or fussy effects. Among Clewell’s most striking pieces are those where the patina takes the shape of flame-like tendrils. (Shapes 334-26, 343-2-6, 369-2-6, 397-2-6.)

Indeed, Clewell’s work is of an entirely different genre than glazed art pottery. It is the antithesis of the gauzy or impressionistic florals produced by Rookwood, Weller et al. Even Heintz Art Metal Shop and Silver Crest, which made patinated bronze vases with sterling silver overlays, rarely approached the contrast, flair and drama of Clewell. (See David H. Surgan, The Heintz Finishing Touch, Style 1900 magazine Vol. 11 No.2 (1998), pp.28-34.) Surely Clewell understood the uniqueness of his work, and like many visionaries, that understanding was what led him to labor in solitude for so many years, seemingly heedless of public recognition.

Just as little has been written about Clewell and his work, you’ll seldom encounter a Clewell vase in a museum. Clewells don’t have the kind of showy handwork that wows the cognoscenti. The masterful and comprehensive survey of American art pottery by Alice Cooney Frelinghuysen, Martin Eidelberg and Adrienne Spinozzi, American Art Pottery: The Robert A. Ellison Collection (2018), contains nary a mention of Clewell.

Moreover, a search of the Smithsonian archives (si.edu/search) for Clewell pottery turned up but a single example, while 558 results appeared for Rookwood pottery. A 2023 exhibition of metal works at the Museum of the American Arts & Crafts Movement, featuring the likes of Dirk Van Erp and Frank Lloyd Wright, contained no Clewells. A curator, asked why, seemed unfamiliar with the name.

A collection of 16 Clewells may be found in his hometown, however, at the Canton Museum of Art (https://www.cantonartcollection.com). Some of those pieces were donated to the museum by Clewell himself.

Regardless of curatorial recognition, Clewell pottery taps squarely into the holistic, somewhat spiritual yet down-to-earth values that define the Arts and Crafts movement. Its elemental, natural qualities give it an expressiveness and character all its own. So whatever twists and turns the fickle tastes of the public might take, to aficionados it is a style that will never get old.

Clewell Markings

Clewell’s patinated ware is generally marked on the bottom with the name “Clewell” or “CW Clewell” scratched in his own distinctive hand with an awl or similar tool, along with shape numbers.

A few pieces bear impressed logos such as those at left (from shapes U(1) and A4) or a paper label (shapes B9, U(15)), or markings impressed by the maker of the blank (shapes 2-6, 827).

A few pieces bear impressed logos such as those at left (from shapes U(1) and A4) or a paper label (shapes B9, U(15)), or markings impressed by the maker of the blank (shapes 2-6, 827).

Just as Clewell was secretive about his methods, he left no notebook of shapes; nor do his markings make his work easy to catalog. Some pieces are unmarked; shape numbers are sometimes difficult to discern (passage of time can be a factor here); shape numbers used are not systematic or intuitive; identical shapes are sometimes given different numbers (compare shapes 259 and 260); and pieces are almost never dated (exceptions are shapes 440-416, 456-416, 456-416(2), 458-416, all of which are dated 1931).

As noted above, Clewell’s never-ending experimentation resulted in widely varying results, harkening back to the ancient, encrusted jug that inspired him. Patinas can be barely discernible or a single color taking over the entire piece. Because of these and other irregularities (shapes U(7), 370-2-6), some of Clewell’s results might be considered subpar. However, Clewell is not known to have ever marked a piece as second quality. Given the somewhat coarse and primitive qualities of his finishes, unexpected variations can be embraced without the denigrating label of “second.”

Unmarked items attributed to Clewell are included on this site if reasonably identifiable as Clewell pottery. Such items are catalogued with the prefix U, as are items bearing the Clewell logo but no number.

Clewell Pricing

Have you heard the old joke about the vagaries of a lawsuit? Joe was sued twice, for paternity and for inability to consummate his marriage—wouldn’t you know, he lost both suits! Such are the vagaries of a lawsuit…

Like lawsuits, art pottery prices are unpredictable, and Clewell is especially so; a piece can pass at auction or on eBay for twice—or half—what a similar piece passed for recently elsewhere.

In the early 2000s Clewell prices soared, exceeding $200 per inch in some cases, before dropping around 2010 to maybe half that amount on average. As of 2026, prices vary widely between $25-$125 per inch. The major auction houses—Rago, Toomey and California Historical Design come to mind—tend to draw markedly higher prices. It must be emphasized however, that prices fluctuate widely based on the characteristics of the individual piece and who is bidding. The market for Clewell is generally tepid, with desirable pieces sometimes languishing on the market and passing on the lower side of the $25-$125 per inch range. The median price is in the range of $50-$60 per inch.

Clewell pieces often exhibit imperfections in the form of vein-like hairline cracks in the metal coating. (Shapes 325-2-6, 370-2-6(2), 399-6.) Whether these occurred in the making or developed later is difficult to determine. While such hairlines reduce market value for some collectors, they can reasonably be viewed as part of the character of the piece, giving rise to buying opportunities. But when the fissures reach the point of being cracks (shape 440-219), or there are losses to the metal coating (shape 260-6), value is impaired by 50% or more.

Some Clewell pieces suffer from flaking or scratching, exposing a tan color under the surface. (Shapes 456-26, 459.) Depending on the extent of the discoloration, such blemishes can be unsightly and reduce the value of the piece.

Use of any cleaning or polishing products is likely to damage the patina, resulting in loss of value.

Clewells are plentiful enough that if you’re in the market, you won’t have to wait long for a chance to score one. In buying, consider size, shape, patina and condition. A cool head and an informed perspective are indispensable—as is the comparable sales information available here.

Sources:

Paul Evans, Art Pottery of the United States (2nd ed. 1987), pp. 56-58.

Marion John Nelson, Art Pottery of the Midwest (1988), pp. 24-25.

Lucile Henzke, Art Pottery of America (4th ed. 2008), pp. 49-50.

Ralph and Terry Kovel, Kovels’ American Art Pottery (1993), pp. 23-24.

Wisconsin Pottery dot org

https://www.cantonartcollection.com/artistbio.php?artist_id=215

For information about Rookwood pottery, see RookwoodDatabase.com.

A patina even Clewell could love: Statue of Revolutionary War officer Nathanael Greene in Stanton Park in Washington, D.C.